Part 4 of 4

From the very start, the educational system of the country was overburdened. Yemen’s official stance on the invasion of Kuwait in 1990 altered the nascent economic condition of the country. There was extreme pressure and unexpected repercussions on Yemen from being at odds with Gulf States and the West on policy matters. In 1991, more than a million Yemenis were expelled from Saudi Arabia and the Gulf as a punishment for Yemen’s refusal to support the military campaign launched against Iraq. This mass expulsion of Yemenis workers coupled with the loss of financial support from the Gulf had a huge negative impact on the country. As unemployment and inflation skyrocketed, Yemen was overwhelmed with the sudden influx of returning workers. The inflation affected everything, for example, powdered milk prices increased from 26 to 182 Yemeni Riyals (Dresch 191). Among these reverberations was the immobilization of the education system.

The pedagogic skills of the country suffered from overpopulation and poor management. According to data gathered by the World Bank and the Ministry of Education, by 1992, it was already clear that male education was more favorable than that of women. Girls made up only 24% of all students in grades 1-9 (Noman 2). With more scrutiny, the numbers reveal that many girls drop out of school; for example, in grade 1, girls make up 31% of all students, whereas by grade 9, they constitute only 11% of all students. Additionally 54% of all six-year-old girls never go to school (Ba’abad 292). Even though these numbers appear scanty, it is still considered an improvement and will continue to grow gradually. Nonetheless, while the northern women were used to the current law, the southern women protested the new decrees on April of 1992. The women united under the Organization for the Defense of Democratic Laws and Freedoms, which is a 5,000 member conglomerate of lawyers and other female professionals, but their protests for reform were snubbed (Molyneux, “Women’s Rights and Political Contingency” 428-9).

1994 Civil War

In April of 1993, parliamentary elections took place. The GPC won the majority with 123 seats, and the Islamic party, known as Islah, won 62 seats while the YSP lost some seats in the south and gained some in the north but overall came in last place winning only 56 seats out of 301. The YSP’s claim to 50% of the power was jeopardized. Now, the Presidential council had two GPC members, two Islah members and only one YSP member. The speaker of the parliament was the prominent Shaykh of Hashid, Abullah Al-Ahmar; one of the leaders of the Islah party. Displeased, Al-Beed (VP), retreated to Hadramawt (a governorate that shares borders with Saudi Arabia at the east of Yemen). This trip alarmed the GPC who feared that Al-Beed would create an alliance with Saudi Arabia. Saleh mobilized his army in preparation for the worst. The new country barely had time to settle and was already well on its way for a towards political upheaval. The YSP prepared and submitted 18 points of demands to be met, while GPC prepared and submitted 19 points to the “Dialogue Committee”, which drafted a constitution that stated the full consolidation of the YSP and GPC’s army. Saleh and Al-Beed agreed on the terms provided by the committee in Oman (Dresch 193-5).

Soon after, war broke out on April 27, 1994 in ‘Amran. By May 21st, Al-Beed declared secession and declared a new country with Aden as its capital. The north, under Saleh, fought to reunite the country. The war ended on July 7th with the fall of Aden, and the escape of Al-Beed and the other secessionist leaders. The results of the war revealed that the majority of the people of Yemen wanted peace and unity but the months of fighting left the city of Aden plundered. According to Molyneux, the south lost much of its “distinctive, modern character” after the war as the event curtailed political diversity in the nation (“Women’s Rights and Political Contingency” 430).

Islah’s Growth in Government and Ramifications on Female Education

Islah, formerly known as al-Tajamu’ Al-Yamani li-l-islah or the Yemeni Reform Grouping, is mainly a northern party (later includes southerners) that stood firmly with Saleh during the Civil War; “[s]everal Islamists claimed that fighting the socialists was jihad or holy war” (Dresch 196). Islah had three powerful representatives that drew supporters from all over the country; Sheikh Abdullah Al Ahmar of Hashid who represented the tribalists, Yasin Al-Qubati who represented the Muslim Brotherhood (no connection to Egypt’s MB), and Abdul Al-Majid Al-Zindani who represented radical Islamists (Dresch 186-7). The party presented itself as a challenger to the GPC and YSP; however, they had strong connections with president Saleh (i.e. Islah’s party secretary, ‘Abd Al-Wahab Al-Ansi, was strongly connected to Saleh). Although Islah is a three-part party, the Salafi influence was always prominent in their policies. For example, prior to the unification, Islah opposed the merger with the south as the radicalists considered them “un-Islamic” (Molyneux, “Women’s Rights and Political Contingency” 426).

As a reward for supporting Saleh and the GPC during the brief conflict, Islah’s influence increased significantly and with that came changes to women’s status. The Minister of Justice was from Islah and stated that women “were totally incompetent in Islamic Law”, so women judges in the south were dismissed or reassigned to other jobs. Also, many members of Islah publicly criticized the nomination of a woman as an undersecretary in the Ministry of Information. Other members declared that women should not serve in the parliament because “God made women emotional and did not give them strong character, and emotion does not suit leadership” ("Yemen: Government Attitude Towards Women”). This argument is still used to this day against women leadership and the United States is used as an example of a powerful country that would not choose a woman as a president.

The educational system after 1994 changed according to Islah’s agenda. Prior to 1994 and since the 1980s, Islah supported and financed religious schools known as Al-Ma’ahid Al-‘ilmiyyah or the Learning Institutions. Many of these institutions had Egyptian teachers and through time were gaining popularity. In 1993; however, they caused a stir in the parliament. The schools were acting independently from the formal educational system and were financed by Saudi money (Molyneux, “Women’s Rights and Political Contingency” 426). As a way of compromise, Saleh struck a deal with Islah; he agreed to finance their salaries as long as they decrease their reliance on Saudi Arabian money and shut down these schools. In turn, Islah agreed to comply as long as they retained control of the Ministry of Education, and so a new educational curriculum was in place.

The country suddenly witnessed an increase in universities in the period following the Civil War as the population settled down. The public universities of Sana’a and Aden had been established since 1970-71 but the majority of public universities were inaugurated following the transitional period in the cities of Taiz, Hudaydah, Ibb, Hadramawt, and Dhamar (see chart 4). The public universities offered an array of scientific, engineering, and humanities majors varying from medicine to business. In 1995, a law was decreed uniting the programs, administrations and objectives of public universities (Ba’abad 356). Coincidentally, many private universities opened their doors to undergraduates in the same period (see chart 5), but their majors were limited. For example, Al-Iman university, a free religious school running on donations, founded by Islah’s Abdul Majeed Al-Zindani offers only two years of Wahhabi instruction. According to the latest data available on public universities in 2002, these private universities do not have any restrictions by the Ministry of Education or supervisions on the standards, rules and regulations because they were created prior to 1996 when university permits took effect (Ba’abadi 366-369). This lack of management allows private universities to do as they wish and to endanger the quality of education that the students are receiving.

Chart 4: Public Universities in Yemen (data based on 2002 findings)

Source: Ba'abad, 'Ali. Al-Ta'aleem Fee Al-Jumhooriah Al Yamaniyah [Education in the Yemeni Republic]. 7th ed. Sana'a: Maktabat Al-Irshad, 2003. 355. Print.

Chart 5: Private Universities in Yemen (data based on 1998/1999 findings)

Source: Ba'abad, 'Ali. Al-Ta'aleem Fee Al-Jumhooriah Al Yamaniyah [Education in the Yemeni Republic]. 7th ed. Sana'a: Maktabat Al-Irshad, 2003. 371. Print.

Along with a contentious structure of education, female agency was undermined. Islah, like many Islamist parties in the region, was well organized and within their party, they had a women’s division that dealt with “women issues”. Islah believed that women’s role was better fit at home and that it is what God preferred. A woman’s primary role is to care for her children and care for her home. Luckily, they did not object to women working, however they insisted that women obtain the permission of their husbands ("Yemen: Government Attitude Towards Women”). Changes in family law increased talaq and polygamy in the south. The new government was accused of diverting aid from the south and investing it in the North which deteriorated the economic status of Aden; causing higher unemployment rates in general, but also amongst women. Many female factory workers were dismissed from their jobs.The previously mentioned General Union of Yemeni Women in the south was accused of taking no action to defend women’s rights. Another “women issue” was co-educational schools, as the party objected to takhallut al-ta’lim or social mixing through education (Molyneux, “Women’s Rights and Political Contingency” 426). Starting 1996, the Minister of Education (an Islah member), gradually ended co-educational classes and recommended that females be taught by women ("Yemen: Government Attitude Towards Women”). Their ideology was capable of infiltrating the constitution as well. A few months following the war, the constitution changed Shari’a from al-masdar al-ra’isi or the main source of legislation to al-masdar al-waheed or the only source of legislation (Molyneux, “Women’s Rights and Political Contingency” 426). Most importantly the marriage age limit, 15 years old, was abolished on the basis that it was “un-Islamic” (Khalife 2).

Female Education during the Past Decade

For southern Yemeni women, education under the Republic of Yemen was disenchanting while for northern women, the system granted educational privileges for the first time. However, educational modifications for women took off in 2001, when the Ministry of Education partnered with NGOs in an attempt to achieve universal basic education by 2015. The Ministry of Education in 2004 decided that it was time to create a special sector for women. Headed by a female deputy minister, the office was staffed by women to monitor and implement female educational plans. Armed with the support of other nations and NGOs, the Ministry of Education had a new budget of only $8,439,452 (Al-Mekhlafey 270-273).

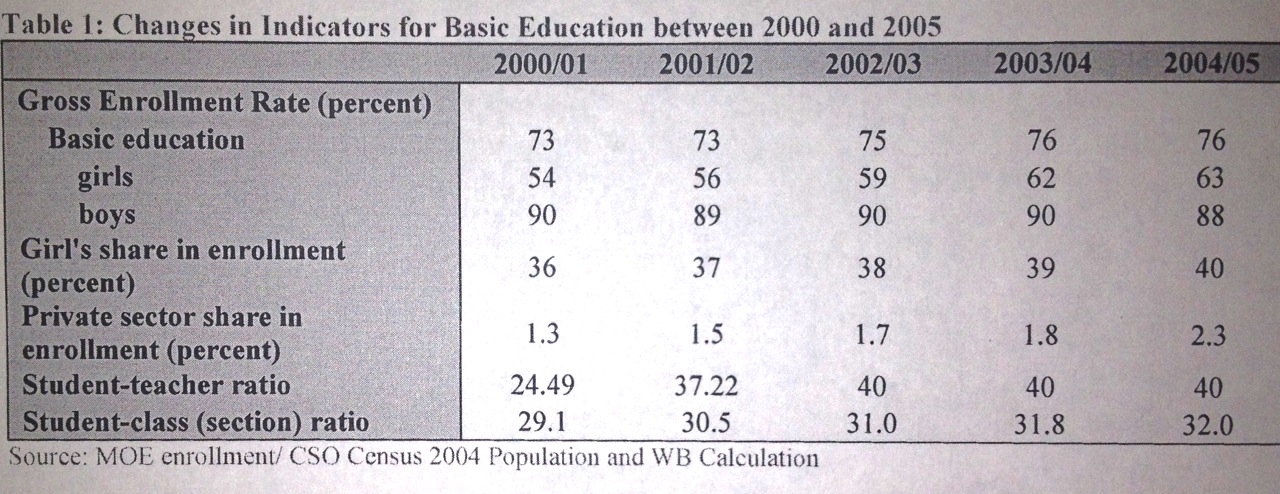

Although the goal was challenging, the efforts spent were fruitful. According to the World Bank, the gross enrollment ratio (GER) for grades 1-9 improved from 65.4% to 75.8% in a two year period from 2004 to 2006. The breakdown of these number reveals that girl education improved as well as the female enrollment rate went from 50.9% to 63.7% (see chart 6 for progress) which narrowed the gender gap from 28.8 to 23.3 for primary education (Al-Mekhlafey).

Chart 6: Changes in Indicators for Basic Education (2000-2005)

Source: Alim, Abdul, Kamel Ben Abdallah, Solofo Ramaroson, Maman Sidikou, and Lieke Van De Wiel. Accelerating Girl's Education in Yemen: Rethinking Policies in Teachers' Recruitment and School Distribution. Working paper. New York: United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), 2007. Print.

A report prepared by UNICEF reveals that although gender parity ameliorated since 2001, the rate of progress will not allow the country to achieve the Millennium Development Goal # 3 (to promote gender equality and empower women) by 2015 (Alim 4-7). Illiteracy in Yemen in 2007 for the entire population above the age of 10 was a staggering 47%; only 59.5% of all females in urban areas and 24.3% of females in rural areas are literate (Alim 9). The gender gap is very small in primary education; however, it increases significantly in higher education. Case in point, 43% of all first grade students were females in the academic year 2003/04; this figure represents 76 girls for every 100 boys, but by the ninth grade, the number decreases to 44 girls for every 100 boys (Alim 8). These numbers reveal that many girls do not continue their education and dropout.

Tomorrow: The current Obstacles Standing the in the path of female education in Yemen.

The two emergent Yemeni states followed dramatically different political philosophies, with South Yemen taking a radical Marxist approach and North Yemen developing a

conservative military government. Still, they had much in common: a heritage of relative isolation from the rest of the world and problems of underdevelopment such as poverty; lack of infrastructure; and lack of basic health and social services, including education... Although the two Yemens shared similar problems and aims, they remained at a political impasse. Both agreed on the goal of a unified state but each aspired to absorb the other. (Boxberger 121-122)

In 1990, the YAR and PDRY merged to form the Republic of Yemen. Saleh maintained his position as president of unified Yemen, while the president of the PDRY, Ali Salim Al-Beed, assumed the position of vice president (Dresch 186). The phase of May 1990 to July 1994 was dubbed by many Yemen experts “the transitional period” where the two ruling parties, the General People’s Congress (GPC) of the North and the Yemeni Socialist Party (YSP) of the South, formulated a vague political action plan called the Program of National Construction and Reform.

Two of the main points concerning women declare the nation’s objective of “providing opportunities for women to study and work” and “promoting the emancipation and freeing of women from traditional customs and traditions in order to enhance their effective participation in society” (“Women’s Rights and Political Contingency” 423). By 1992, a new family law was put into effect across the nation. This law was almost identical to the North’s Family Law but with minor changes based on the Arab League’s Mashru’ Qanun al-Ahwal al-Shakhsiyya al-’Arabiyya Al-muwahid or the Unified Model of Arab Personal Statute Law. The new country had a new constitution where Islam is the official religion of the state and Shari’a is the main source of law.

EducationTwo of the main points concerning women declare the nation’s objective of “providing opportunities for women to study and work” and “promoting the emancipation and freeing of women from traditional customs and traditions in order to enhance their effective participation in society” (“Women’s Rights and Political Contingency” 423). By 1992, a new family law was put into effect across the nation. This law was almost identical to the North’s Family Law but with minor changes based on the Arab League’s Mashru’ Qanun al-Ahwal al-Shakhsiyya al-’Arabiyya Al-muwahid or the Unified Model of Arab Personal Statute Law. The new country had a new constitution where Islam is the official religion of the state and Shari’a is the main source of law.

From the very start, the educational system of the country was overburdened. Yemen’s official stance on the invasion of Kuwait in 1990 altered the nascent economic condition of the country. There was extreme pressure and unexpected repercussions on Yemen from being at odds with Gulf States and the West on policy matters. In 1991, more than a million Yemenis were expelled from Saudi Arabia and the Gulf as a punishment for Yemen’s refusal to support the military campaign launched against Iraq. This mass expulsion of Yemenis workers coupled with the loss of financial support from the Gulf had a huge negative impact on the country. As unemployment and inflation skyrocketed, Yemen was overwhelmed with the sudden influx of returning workers. The inflation affected everything, for example, powdered milk prices increased from 26 to 182 Yemeni Riyals (Dresch 191). Among these reverberations was the immobilization of the education system.

The pedagogic skills of the country suffered from overpopulation and poor management. According to data gathered by the World Bank and the Ministry of Education, by 1992, it was already clear that male education was more favorable than that of women. Girls made up only 24% of all students in grades 1-9 (Noman 2). With more scrutiny, the numbers reveal that many girls drop out of school; for example, in grade 1, girls make up 31% of all students, whereas by grade 9, they constitute only 11% of all students. Additionally 54% of all six-year-old girls never go to school (Ba’abad 292). Even though these numbers appear scanty, it is still considered an improvement and will continue to grow gradually. Nonetheless, while the northern women were used to the current law, the southern women protested the new decrees on April of 1992. The women united under the Organization for the Defense of Democratic Laws and Freedoms, which is a 5,000 member conglomerate of lawyers and other female professionals, but their protests for reform were snubbed (Molyneux, “Women’s Rights and Political Contingency” 428-9).

1994 Civil War

In April of 1993, parliamentary elections took place. The GPC won the majority with 123 seats, and the Islamic party, known as Islah, won 62 seats while the YSP lost some seats in the south and gained some in the north but overall came in last place winning only 56 seats out of 301. The YSP’s claim to 50% of the power was jeopardized. Now, the Presidential council had two GPC members, two Islah members and only one YSP member. The speaker of the parliament was the prominent Shaykh of Hashid, Abullah Al-Ahmar; one of the leaders of the Islah party. Displeased, Al-Beed (VP), retreated to Hadramawt (a governorate that shares borders with Saudi Arabia at the east of Yemen). This trip alarmed the GPC who feared that Al-Beed would create an alliance with Saudi Arabia. Saleh mobilized his army in preparation for the worst. The new country barely had time to settle and was already well on its way for a towards political upheaval. The YSP prepared and submitted 18 points of demands to be met, while GPC prepared and submitted 19 points to the “Dialogue Committee”, which drafted a constitution that stated the full consolidation of the YSP and GPC’s army. Saleh and Al-Beed agreed on the terms provided by the committee in Oman (Dresch 193-5).

Soon after, war broke out on April 27, 1994 in ‘Amran. By May 21st, Al-Beed declared secession and declared a new country with Aden as its capital. The north, under Saleh, fought to reunite the country. The war ended on July 7th with the fall of Aden, and the escape of Al-Beed and the other secessionist leaders. The results of the war revealed that the majority of the people of Yemen wanted peace and unity but the months of fighting left the city of Aden plundered. According to Molyneux, the south lost much of its “distinctive, modern character” after the war as the event curtailed political diversity in the nation (“Women’s Rights and Political Contingency” 430).

Islah, formerly known as al-Tajamu’ Al-Yamani li-l-islah or the Yemeni Reform Grouping, is mainly a northern party (later includes southerners) that stood firmly with Saleh during the Civil War; “[s]everal Islamists claimed that fighting the socialists was jihad or holy war” (Dresch 196). Islah had three powerful representatives that drew supporters from all over the country; Sheikh Abdullah Al Ahmar of Hashid who represented the tribalists, Yasin Al-Qubati who represented the Muslim Brotherhood (no connection to Egypt’s MB), and Abdul Al-Majid Al-Zindani who represented radical Islamists (Dresch 186-7). The party presented itself as a challenger to the GPC and YSP; however, they had strong connections with president Saleh (i.e. Islah’s party secretary, ‘Abd Al-Wahab Al-Ansi, was strongly connected to Saleh). Although Islah is a three-part party, the Salafi influence was always prominent in their policies. For example, prior to the unification, Islah opposed the merger with the south as the radicalists considered them “un-Islamic” (Molyneux, “Women’s Rights and Political Contingency” 426).

As a reward for supporting Saleh and the GPC during the brief conflict, Islah’s influence increased significantly and with that came changes to women’s status. The Minister of Justice was from Islah and stated that women “were totally incompetent in Islamic Law”, so women judges in the south were dismissed or reassigned to other jobs. Also, many members of Islah publicly criticized the nomination of a woman as an undersecretary in the Ministry of Information. Other members declared that women should not serve in the parliament because “God made women emotional and did not give them strong character, and emotion does not suit leadership” ("Yemen: Government Attitude Towards Women”). This argument is still used to this day against women leadership and the United States is used as an example of a powerful country that would not choose a woman as a president.

The educational system after 1994 changed according to Islah’s agenda. Prior to 1994 and since the 1980s, Islah supported and financed religious schools known as Al-Ma’ahid Al-‘ilmiyyah or the Learning Institutions. Many of these institutions had Egyptian teachers and through time were gaining popularity. In 1993; however, they caused a stir in the parliament. The schools were acting independently from the formal educational system and were financed by Saudi money (Molyneux, “Women’s Rights and Political Contingency” 426). As a way of compromise, Saleh struck a deal with Islah; he agreed to finance their salaries as long as they decrease their reliance on Saudi Arabian money and shut down these schools. In turn, Islah agreed to comply as long as they retained control of the Ministry of Education, and so a new educational curriculum was in place.

The country suddenly witnessed an increase in universities in the period following the Civil War as the population settled down. The public universities of Sana’a and Aden had been established since 1970-71 but the majority of public universities were inaugurated following the transitional period in the cities of Taiz, Hudaydah, Ibb, Hadramawt, and Dhamar (see chart 4). The public universities offered an array of scientific, engineering, and humanities majors varying from medicine to business. In 1995, a law was decreed uniting the programs, administrations and objectives of public universities (Ba’abad 356). Coincidentally, many private universities opened their doors to undergraduates in the same period (see chart 5), but their majors were limited. For example, Al-Iman university, a free religious school running on donations, founded by Islah’s Abdul Majeed Al-Zindani offers only two years of Wahhabi instruction. According to the latest data available on public universities in 2002, these private universities do not have any restrictions by the Ministry of Education or supervisions on the standards, rules and regulations because they were created prior to 1996 when university permits took effect (Ba’abadi 366-369). This lack of management allows private universities to do as they wish and to endanger the quality of education that the students are receiving.

| University Name | Initiation Year | # of Colleges | # of Sections |

| Sana’a | 1970 | 17 | 95 |

| Aden | 1970 | 15 | 88 |

| Hudaydah | 1995 | 10 | |

| Taizz | 1994 | 6 | |

| Ibb | 1996 | 8 | |

| Hadramawt | 1996 | 9 | 37 |

| Dhamar | 1996 | 11 | 39 |

| Total | 76 |

Chart 5: Private Universities in Yemen (data based on 1998/1999 findings)

| University Name | Initiation Year | # of Colleges | # of Sections |

| Al-Iman | 02/17/1993 | 4 | 28 |

| College of Shari’a | 12/29/1993 | 1 | 1 |

| Al-Watanyah | 01/02/1994 | 7 | 19 |

| University of Science and Technology | 01/12/1994 | 10 | 40 |

| Al-Ahqaq | 02/08/1998 | 2 | 3 |

| Higher College for Qur’an | 04/15/1994 | 1 | 1 |

| Saba’ | 08/11/1994 | 3 | 5 |

| Al-Yemeniah | 10/09/1995 | 3 | 8 |

| University of Applied Sciences | 10/09/1995 | 8 | 36 |

| Queen Arwa University | 01/06/1996 | 7 | 38 |

| Total | 46 | 159 |

Along with a contentious structure of education, female agency was undermined. Islah, like many Islamist parties in the region, was well organized and within their party, they had a women’s division that dealt with “women issues”. Islah believed that women’s role was better fit at home and that it is what God preferred. A woman’s primary role is to care for her children and care for her home. Luckily, they did not object to women working, however they insisted that women obtain the permission of their husbands ("Yemen: Government Attitude Towards Women”). Changes in family law increased talaq and polygamy in the south. The new government was accused of diverting aid from the south and investing it in the North which deteriorated the economic status of Aden; causing higher unemployment rates in general, but also amongst women. Many female factory workers were dismissed from their jobs.The previously mentioned General Union of Yemeni Women in the south was accused of taking no action to defend women’s rights. Another “women issue” was co-educational schools, as the party objected to takhallut al-ta’lim or social mixing through education (Molyneux, “Women’s Rights and Political Contingency” 426). Starting 1996, the Minister of Education (an Islah member), gradually ended co-educational classes and recommended that females be taught by women ("Yemen: Government Attitude Towards Women”). Their ideology was capable of infiltrating the constitution as well. A few months following the war, the constitution changed Shari’a from al-masdar al-ra’isi or the main source of legislation to al-masdar al-waheed or the only source of legislation (Molyneux, “Women’s Rights and Political Contingency” 426). Most importantly the marriage age limit, 15 years old, was abolished on the basis that it was “un-Islamic” (Khalife 2).

For southern Yemeni women, education under the Republic of Yemen was disenchanting while for northern women, the system granted educational privileges for the first time. However, educational modifications for women took off in 2001, when the Ministry of Education partnered with NGOs in an attempt to achieve universal basic education by 2015. The Ministry of Education in 2004 decided that it was time to create a special sector for women. Headed by a female deputy minister, the office was staffed by women to monitor and implement female educational plans. Armed with the support of other nations and NGOs, the Ministry of Education had a new budget of only $8,439,452 (Al-Mekhlafey 270-273).

Although the goal was challenging, the efforts spent were fruitful. According to the World Bank, the gross enrollment ratio (GER) for grades 1-9 improved from 65.4% to 75.8% in a two year period from 2004 to 2006. The breakdown of these number reveals that girl education improved as well as the female enrollment rate went from 50.9% to 63.7% (see chart 6 for progress) which narrowed the gender gap from 28.8 to 23.3 for primary education (Al-Mekhlafey).

Chart 6: Changes in Indicators for Basic Education (2000-2005)

Source: Alim, Abdul, Kamel Ben Abdallah, Solofo Ramaroson, Maman Sidikou, and Lieke Van De Wiel. Accelerating Girl's Education in Yemen: Rethinking Policies in Teachers' Recruitment and School Distribution. Working paper. New York: United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), 2007. Print.

A report prepared by UNICEF reveals that although gender parity ameliorated since 2001, the rate of progress will not allow the country to achieve the Millennium Development Goal # 3 (to promote gender equality and empower women) by 2015 (Alim 4-7). Illiteracy in Yemen in 2007 for the entire population above the age of 10 was a staggering 47%; only 59.5% of all females in urban areas and 24.3% of females in rural areas are literate (Alim 9). The gender gap is very small in primary education; however, it increases significantly in higher education. Case in point, 43% of all first grade students were females in the academic year 2003/04; this figure represents 76 girls for every 100 boys, but by the ninth grade, the number decreases to 44 girls for every 100 boys (Alim 8). These numbers reveal that many girls do not continue their education and dropout.

Tomorrow: The current Obstacles Standing the in the path of female education in Yemen.

No comments:

Post a Comment